Welcome, Friend, to Grayback Diary, the fictional diary entries of David Tooms during the very real War Between the States. He began this diary in 1861.The war and these entries are nearly over. The events in the diary are based on primary sources such as records from the National Archives and Library of Congress. Thanks to all for reading.

Wednesday, May 20, 2015

Saturday, May 16, 2015

"We will drink stone blind..."

Tuesday, May 16, 1865, Parker's Ferry, Charleston Road

My leg is better now. I did not do a great deal of walking yesterday. Instead, I spent most of the day sitting along the road. I feel better for it even though it will take another day more to reach home. The road was not crowded. For the entire time that I sat there, which was some hours, I might have seen perhaps fifty or sixty people. Only a few had wagons and all were pulled by mules. I saw not a single horse. I have not seen a horse since those bushwhackers tried to rob and kill us last week. Some folks had carts with all their possessions which did not appear to be many. One cart was being drawn by a mule, the rest were being pushed by their owners.

As they passed by, they would see me and wave. A few would halloo at me. One, John J. Oaks from the Forty-third Alabama, stopped and we talked for awhile. We discovered, as we talked, that we had been in many of the same battles.. He, like myself, was at the Petersburg trenches. We ate from our meager rations and he smoked his pipe afterwards. We bade our good-byes to each other and he was back on the road heading south to Mobile.

|

| Battle flag of the 43rd Alabama. |

As we chatted, I could not help but think that although we had never met before and we were in widely separated units, we had so very much in common. We ate the same rations, both official an not. We sang the same songs. We marched the same, were clothed the same, or not as circumstances dictated. We suffered the same illnesses and suffered the same treatments. We both lost comrades to battle and disease. Both of us came close to our last day on earth several times. We have survived everything the Yankees threw at us.

Even if there are still Confederates in the field somewhere, this cruel war is over. We who have lived are scattering our numbers all throughout the South. None of us will ever serve with each other again. Even so, we are linked together, bonded forever by the common experiences of comrades in war. I suppose there will be reunions from time to time where we who are still here will tell stories, getting ever bigger with each passing year. We will drink toasts to our fallen comrades, our Confederacy, our wives and sweethearts, ourselves, anything. We will drink stone blind and do it all again at the next reunion.

|

| Confederate veterans from Arkansas. |

|

| Florida. |

|

| Georgia. |

|

| Mississippi. |

|

| North Carolina. |

|

| West Virginia. |

|

| Tennessee. |

|

| Patrick County, Virginia, 1900. |

The children will set at our feet and gaze at us in awe as we tell of our exploits and the hazards we lived through. They will believe everything we say no matter what. The womenfolk and the stay-at-home men will hear us as we talk amongst ourselves but will understand little. For those who have seen the elephant, a certain word or phrase, a certain wink or nod, and that is all it will take to understand some event or circumstance all have shared witness to. To that regard, I suppose the Yankees must be included in this circle.

|

| Gettysburg. |

|

| Brothers again. |

Speaking of the Yankees, I suppose that we will have to get along with them now that we are brothers again. We are supposed to go home, tend to our fields and stores, and endeavor to be good citizens, all of us. Too much blood as been spilled on both sides to do otherwise.

Four very long years ago, I had started this diary with the purpose of providing a chronicle of persons, places and events that I can refer to in my old age. I hope to find some comfort in this. Was it but yesterday that I, an old recruit, was drilling my own squad of new recruits?

I have seen two wars. May I never see a third.

Some day, there will be just one of us left. May that last one standing toast those who have gone before.

I Send you These Few Lines

The war was hard on all concerned. Numbers do not tell the whole story but they do give some perspective to events. For Tooms' regiment, the 12th Carolina, the brigade historian records that:

21 officers and 260 men were killed during the war with 2 officers and 182 men dying form disease for a total of 465 dead. Some 652 were wounded. 26 officers resigned and 169 enlisted men were discharged. At Appomattox, the parole rolls record that 10 officers and 150 enlisted men surrendered.

For the Hancaster Hornets, Company I of the 12th, the following comes from the muster rolls of the company held at the National Archives repository at College Park, Maryland. The rolls, which are by no means complete, shows that 7 officers and 121 enlisted men served during the war. Of these, no officers were killed by enemy action or disease but 18 enlisted men were killed in combat and 5 by disease. Officers had the privilege of resigning their commissions and three did. A further 11 enlisted men were discharged for medical reasons. Transfers to other units accounted for 1 officer and three enlisted men. Lastly, four enlisted men deserted.

For the company paroles issued at Appomattox, one officer and 29 enlisted men are listed.

There are still unsurrendered Confederates left but not for long. The last major surrender will take place west of the Mississippi River on May 26, 1865. The war will not be officially declared to be at an end until April 2, 1866 when President Andrew issues a proclamation to that effect for the seceded states.

|

| General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of all Confederate troops west of the Mississippi. He surrendered his command in May of 1865. His was the last large surrender of the war. |

Except Texas.

Texas would be added by the President to the list of states no longer in rebellion on August 20, 1866.

John J. Oaks was in Company I of the 43rd Alamaba. The regiment was a western theatre unit, raised in Mobile. It served with the Army of Tennessee until late in 1863 when it was part of Bushrod Johnson's division that was transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia where it remained for the duration of the war.

|

| Major General Bushrod Johnson. |

Because Tooms had seen prior service in the Mexican War, he was given the rank of lance corporal and a squad of recruits to drill at Camp Lightwood Knot Springs in Columbia, South Carolina. In the squad, besides Tooms, were Burrell Hancock, Thomas Duncan, William Beckham, William Caston, John White and Philip Shehane. Hancock would prove to be Tooms' best friend during the war. He was one of the original members of the, "Dandy Eights Mess."

Of these six:

Hancock would be paroled at Appomattox.

Beckham deserted.

White would be captured at Petersburg in March of 1865 and released in June.

Duncan was captured at Spottsylvania in 1864 and released in June of 1865.

Caston died in a Charleston hospital on April 29, 1862.

Shehane was discharged in September of 1864, reason unknown.

During the war, Tooms and seven of his pards would form a mess called the, "Dandy Eights." The shared bonds mentioned above in Tooms diary entry would be strengthened by groups of soldiers who form a mess, for purposes of cooking and consuming their rations. The original eight were Tooms, Hancock, Duncan, mentioned above, plus William Barton, Sr., William Barton, Jr., Dennis Castles, Troy Crenshaw, John Holton. Of these:

William Barton, Sr. was killed in action, July 1, 1863 at Gettysburg.

William Barton, Jr.was killed in action, May 6, 1864.

Dennis Castles deserts in February of 1865.

Troy Crenshaw disappears from the records after January, 1864.

John Holton disappears from the records after December, 1863.

Of those Lancaster Hornets that survived the war:

Burrell Hancock married Sarah Emeline Garrison Hancock on April 6, 1879. He had been married before the war to Nancy Missouri Cauthen. On October 8, 1899, Hancock passed. In September of 1920, his widow files for a South Carolina pension.

Troy Crenshaw passed on July 3, 1879. His widow, Haseltine, whom he had married in 1858, filed for a South Carolina pension.

William A. Marshall, born October 20, 1845, would file for a state pension in 1919.

J. W. Denton and Isaac T. Vincent would apply for admission to the state Soldier's Home in 1910. Vincent is buried in Beaver Creek Cemetery, Lancaster County.

Simon H. Huey (Huley) was buried in Tirzah Pres. Union Cemetery in 1897.

William T. Sistare passed in 1920 and is buried in Douglas Pres. Cemetery in Lancaster.

John L. Barton passed in 1922 and is buried in Lancaster at the Westside Cemetery.

N.B. Vanlandingham, the Hornets' original company commander went to be with his boys in 1893. He is at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Lancaster County.

Robert J. Hagins passed in 1899 and is buried in Laurelwood Cemetery, Rock Hill, South Carolina.

Wesley Blackmon is buried in Flint Hill Baptist Cemetery, Fort Mill, South Carolina.

Both Lieutenant James S. Williamson and Corporal Joseph H. Flynn, played major parts in this blog both surrendered at Appomattox but I have found no record of any post-war activity for either of them.

There remains one Hornet who has not been properly accounted for. As of this date, he is in Charleston County, South Carolina. His home is in Beaufort County. There is one more county, Colleton, to go through before reaching home.

And one last thing about Jefferson Davis. On this date, 150 years ago, the ex-Confederate president, now prisoner, arrived by steamship at the United States Navy base on Hilton Head Island en route to Washington, D.C. Hilton Head is in Beaufort County. Old Jeff Davis has beat Tooms home.

|

| Jefferson Davis. |

Thursday, May 14, 2015

"They are worse than Yankee bullets."

|

| A post-war image of Charleston ladies tending to the graves of the Confederate dead. |

Sunday, May 14, 1865, Savannah Road.

This wounded leg of mine is slowing me down. It is not a serious wound but it is enough to give me trouble. I will rest here along the road and write this while I do. If I should fall asleep, I will not complain.

It is unlikely that I will fame into slumber. This is rice country and the mosquitoes must number in the many dozens of millions.They are worse than Yankee bullets.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to state that this used to be rice country. I have seen, since leaving Charleston, little evidence that any fields of any sort are being planted or tended. While all is peaceful, it is also very haunting. I have encountered a very few people since leaving Charleston. I say no. I have but three days rations hidden away in my pack and it is perhaps six days to home. Not knowing if I can be re-supplied between here and home, I must be frugal.

It was hard to say good-bye to my comrades from the First. Although I have not known them long, they are all first rate. It was probably harder for them to stay than for me to go. Charleston has been devastated much the same as Columbia, maybe worse. Along the Battery, I could see the occasional home that had been struck by Yankee artillery fire.

|

| Homes along Battery Row, outside the area affected by the Great Fire. This home was damaged by Union artillery fire. |

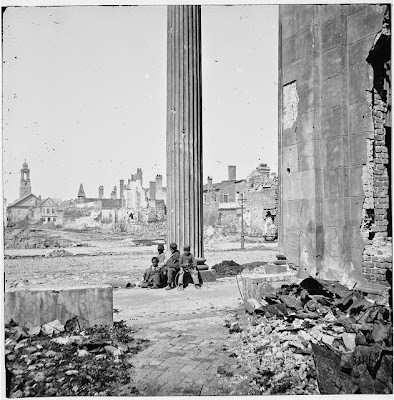

The greatest damage suffered by Charleston during the war came not from the Yankees but from the same thing that has wiped out great areas of Columbia, fire. Upon seeing the devastated areas, I asked aloud to no one in particular if the Yankees intended to burn out the entire South. McGuire volunteered that there was a great fire that laid waste to the city. A band of destroyed buildings cut Charleston across the middle from river to river.

|

| Part of the burned out district of Charleston. |

|

| Interior ruins of St John and St Finbar Church, in the burnt district. |

|

| Charleston burnt district. |

I found it utterly amazing that for the four years of this war, so much of the destroyed district remained so. For reasons unknown to this poor high private, no repairs or re-construction was attempted. Did the war drain away everything from the home front?

I would have liked to have been able to visit Fort Moultrie but that would have been several miles ut of my way. It was there that I received my first taste of this war with the Star of the West.

|

| Steamship Star of the West. |

In exchange for something to eat, I surrendered my carbine. It is just as well as I had only six rounds.

If I do not move this tired old body soon, I certainly will fall asleep.

I Send You These Few Words.

In December of 1861, there occurred what became known as the Great Fire of 1861. Sources differ as to the cause and where it started. Some 600 buildings were destroyed and most of them stayed destroyed for the duration of the war.

|

| Circular Church, in the burnt district. |

|

| Circular Church, April, 2015. |

|

| Looking from the waterfront down Vendee Range. Union shells first struck Charleston in this area during the siege in 1863. |

|

| Same view from the waterfront, April, 2015. |

|

| O'Connor House, April, 2015 |

Tooms did not mention seeing Fort Sumter, or what was left of it. The fort was so shelled by Union artillery that it was never rebuilt to the original design. Its' modern form, after restoration, represents only part of what used to be.

|

| Fort Sumter before the bombardment. |

|

| Fort Sumter after the bombardment. |

|

| Interior, after the bombardment. |

|

| Sumter today. |

|

| Sallyport of Fort Moultrie after the siege. |

|

| Fort Moultrie sallyport, April, 2015. |

Tooms is on his own now. Everyone in the party going from Columbia to Charleston lived in or near Charleston and have no reason to travel any further. They will go home to get their lives up and running again. Tooms is not yet in a position to do this. Tooms will have to be patient and wait until he reaches his home in Beaufort. With that leg of his, he should be there in four days. Five tops.

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

"We shot them down like dogs."

|

| This image, from the Library of Congress, does not identify the Confederate by name but does identify his unit. The 1st Mississippi Cavalry Battalion served west of the Appalachians. |

Friday, May 13, 1865, Orangeburg County

For us, this war was supposed to be over. Our Lee had surrendered us and the Yankees paroled us to go home without a trip to a prisoner of war camp. We had properly signed parole papers that permitted us to return home in peace and stay there in peace. Others may still be in the field, fighting, but not us.

The war came back to us today at Cameron Crossroads in this county. As the ten of us were making our way (I cannot say that we were marching), towards Charleston on the turnpike, we heard hoofbeats coming towards us from somewhere behind us. They sounded as if there was deliberation in their movement. We could not tell if these were Yankees, renegade or otherwise. Even if they had legitimate business for their being on this road, eight of us were armed, and once the Yankees saw us, they might open fire, capture us and send us all to prison.

Captain Kelly quickly gave us orders. Five of us, with all of the rifles, would go hide in the brush along the road. The remaining five, all without arms, except Captain Brailsford who kept his pistol after the surrender, would stay on the side of the road opposite those hidden. If their intentions were peaceful, everyone would go their own way. If otherwise, they would receive a warm reception.

We had not long to wait. No sooner had Captain Kelly and his men hid themselves than the party of horsemen caught up to us and reined themselves in. They were Confederate cavalry, a dozen of them and all armed. Their lieutenant addressed our captain in terms no inferior officer should use with a superior. Their lieutenant, a disgrace to the uniform, demanded our surrender. He stated that they were Wheeler's men and we were about to be separated from anything they deemed of use to them. We were to comply or be killed. Their bushwhacking leader noticed the captain's pistol and demanded he surrender it to him.

Our captain refused, stating that Southerner should not rob fellow Southerners. The renegade said that he would take the pistol either before or after he kills the captain, that it made no difference to him.

Upon hearing this, Captain Kelly ordered his men to open fire. After discharging their rifles, some reloaded while the others took the spare rifles and fired again. I suppose that this made the bushwhackers think that they were outnumbered. They turned to fire back but we had the upper hand. We shot them down like dogs. A few shots were fired in our direction. I was hit by one of them. I was wounded but not badly so. My wound did not stop me from diving for cover into the brush as did all of us on the road except Captain Brailsford who managed to discharge his pistol at the robbers.

In less than a minute this little skirmish was over. Of their dozen, eight were shot dead from their saddles including their leader. The other four, one appearing to be wounded, charged back the way they came. We fired a few rounds in their direction as they fled but we probably did not hit anyone.

Cleapor attended to my wound with a sock from my pack. On our side, I was the only casualty.

My wound is not at all serious. No bone was struck, praise be. Both my legs are still attached but my pace will be slowed, I'm sure.

Brown and McGuire went over to the dead to see what we might find useful. Captain Kelly stopped them. He said that we should not degrade the South our ourselves by descending to their level. He did permit us to take anything edible and any weapons so that all of us would be armed should there be other such encounters. My own musket, in the hands of Samson, was struck in the stock and destroyed. We are all armed now, including myself. I have a carbine which had come to the Confederacy via our overseas friends in the old country. Brown inspected it and pronounced it first rate.

We are now in a barn without a roof for the night. Three of us, armed, are standing watch. Our supper was adequate in quantity if not in quality, our rations being supplemented by that earlier incident. Tomorrow, we will again take to the road to Charleston.

I cannot but help to laugh. During this entire war, through several severe battles, with my comrades falling all around me, no enemy bullet found me. The one and only time that I am shot and it happens to me after the war is over from one who used to be on our side.

Charleston by Sunday.

I Send You These Few Lines.

Cameron Crossroads in now located in Calhoun County, created in 1908 from Orangeburg County.

The county is named after former Vice-President and Senator John C. Calhoun.

|

| John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. |

It is hard to say which side Wheeler and his men were on during the war. Wheeler was touted as a daring and capable cavalry commander but a poor disciplinarian. Some of his men got into a firefight with the 45th North Carolina while the former was attacking a Confederate storehouse. D.H. Hill, a Confederate general officer, stated, "The whole of Georgia is full of bitter complaints of Wheeler's cavalry."

|

| Joe Wheeler, in 1865,, was promoted to Lieutenant General in spite of the reputation of his men. |

|

| Daniel Harvey Hill was just one of many Southerners with harsh things to say about Wheeler. |

Tooms' new firearm is a Maynard carbine. Produced in calibers .50 and .52, it was touted a a very good weapon, favored by Southern cavalrymen. It was not produced in great numbers, perhaps 20,000 total both before and during the war with 3,000 being used in Confederate service. It fired a metallic cartridge which was rare for Southern arms. Being a breech-loader, also a rarity, gave the cavalrymen a rate of fire that was much faster than a muzzle-loader.

|

| Maynard carbine. The lever, when down, would tilt the barrel downward to allow the shooter to load a fresh cartridge into the breech. |

The war is becoming much, much smaller. Tooms could not know that the last major Confederate force left east of the Mississippi has surrendered. Richard Taylor, son of President Zachary Taylor and brother-in-law to Jefferson Davis via Davis' first wife. Taylor's Department of Alabama, Georgia and East Mississippi surrendered on May 8.

|

| A post-war image of former Lieutenant General Richard Taylor. |

Confederate forces still remain in the field west of the Mississippi but their turn is coming.

Jefferson Davis and his party, all prisoners since their capture on May 10, are in Macon, Georgia en route to Savannah. It may not be very clear to the reader why I keep mentioning the ex-Confederate President when supposedly, the last connection between Davis and Tooms was on April 27. See the diary entry Tooms made on that same date for details. I discovered one other connection not too long ago and will include it in this blog when the time comes. There's some talk about a new historical marker to this effect.

Between now and then, Tooms and his comrades still have to get to Charleston without any more trouble. And after that, Tooms will be on his own.

Sunday, May 10, 2015

"...pork and crackers."

|

| This well-armed and probably early-war Confederate is one of the unidentified images from the Library of Congress. |

Wednesday, May 10, 1865, Hammond Crossroads

We had to leave Columbia, and not just because we want to go home. There is nothing there anymore. There was nothing there to keep us so this morning, we left the capital city. Those of us whose homes were nearby left the party to return to home and hearth. The rest of us wanted to revitalize ourselves before leaving for Charleston. Rations were foremost in our mind as our haversacks were nearing empty. We also needed a place to sleep as it was too late to resume our travel.

We were hoping that, even after the fire that there Yankees set, there would be at least one government storehouse operating under the jurisdiction of the Commissary Department. To this end, we made our way to such a storehouse near the railway station. It was there that we met a Major

Rhett of the Quartermaster Department. He confirmed what we already knew from our own observations. There was nothing to be had; the storehouse was all burned up. He said that we could stay inside the burnt hulk as it provided some shelter.

Once we entered, we quickly began looking for anything that could be consumed by hungry soldiers. We moved rubble and burned timbers in our efforts. We found, after much exertion which further famished us, one box of hardtack crackers and a barrel of salt pork. Both box and barrel had been ruptured and a good deal of the contents were spoiled. Out came our pocket knives and off came the spoiled parts. Had we been much more hungry, we would not have cared.

Before building a cook fire, we had to clear off a circle on the dirt floor lest we burn down Columbia again. There was no end of usable firewood around us. There was no water to drink nearby so a water party was formed with all our canteens. Half of us, that is to say, five, as there are only ten of us left, were to make our way to the river while the other five stayed in the storehouse to guard our very invaluable valuables. I was part of the water party and all of us were armed.

We experienced no trouble in filling our canteens but it was difficult finding good water. All those left behind were relieved to see us and not just because we had water. We cooked all we could by way of the discovered pork and crackers and packed as much in our haversacks as would fit for the morrow which is today.

When we left the storehouse, after breakfast, we went to the river to fill our canteens before resuming our march. We made it to the Columbia-Charleston Turnpike and turned there. This is a turnpike in name only. It is little better than a wide trail. Some of us will be losing our shoes before we reach Charleston.

There are just ten of us now, less than half of what left Lancaster on the fourth. Among us are two captains, a first sergeant, an Ordnance Sergeant and six high privates. Everyone served with the First. I am the only one from the Twelfth. They all seem like good men. Five of us, including Captain Kelly, have been wounded in combat with the enemy. Samson has a leg wound that bothers him as we march. We take turns shouldering his knapsack and rifle. Hw would do the same for us.

We are here for the night. This place, this crossroads, is nothing at all. There are no intact buildings present . Tomorrow, we will leave this place. We have told ourselves that we will be on half-rations until we arrive at Charleston. This is nothing; we have been on short rations for most of the war.

God willing, we will be in Charleston in four days.

I Send You These Few Lines.

This new party of travelers consist of nine members of Company K and Company L plus some field and staff personnel of the 1st South Carolina Regiment. Of the 10 companies of the 1st, two, these two, were raised in Charleston, the rest coming from other areas of the state. All during the war, perhaps as many as 200 soldiers served in these two Charleston Companies. Of these 200, only these nine are left. Company K is represented by two men, Michael McGuire and William Aiken.

The two captains are William Aiken Kelly and Edward D. Brailsford. Kelly received a gun shot wound above the clavicle in May of 1864. The first sergeant is Patrick Henry Reilly who was wounded twice during the war. Samson is Abraham J. Samson who took a gun shot wound to the right thigh in 1864. He was also captured at Falling Waters, Maryland at the conclusion of the Gettysburg campaign. John H. Howell, a fellow Hornet from Tooms' company, was captured at Falling Waters. He was later exchanged, returned to duty and wounded a few days before the fall of Petersburg.

The remaining members of this marching and (sans) chowder society are Hezell W. Crouch, Frederick W. Leseman, John Cleapor, Ordnance Sergeant Benjamin F. Brown and the diarist, David Tooms.

Major Roland Rhett was a Quartermaster Department officer stationed in Columbia during the burning. The Commissary building the party stayed in was located at the northeast corner of Gervais and Wayne in Columbia.

The observations that Tooms made concerning the turnpike were quite correct. The road from Columbia to Charleston was chartered years before the war and rapidly fell into neglect. The route is now US 176, otherwise known as the Old State Road.

Today, 150years ago, Jefferson Davis and his party were captured by Union cavalry near Irwinville, Georgia.

Four days to a safe haven in Charleston. Tooms has five or six more days to go.

Thursday, May 7, 2015

"Columbia has been burnt to H--l."

|

| This unidentified image of a Confederate soldier comes from the Library of Congress. |

Sunday, May 7, 1865, Columbia

We are getting closer to getting home, some of us much closer than others.

We arrived here in Columbia yesterday. I could easily have bypassed this city and not been so disheartened as I am now and I am not the only one. It is the worst for those in our humble party who live in the capital city or anywhere nearby. This is a horrible place. Columbia has been burnt to H--l.

The Yankees know how to torch or city. It is one of the things that they do very well.

After we left Camden, it was evident that Sherman's men had passed through the area.We passed by farmhouses, barns and outbuildings, both burned up and intact. We could decipher no rhyme or reason to this.

|

| Major General William T. Sherman. |

We could smell Columbia before we saw it. There has been mush devastation here. Those without shelter are many. There are many refugees here and all are hungry. The Yankees have reduced this once-fine city to a desolate wasteland. We would never do such a thing.

|

| Columbia ruins. |

|

| Ruins of Christ Episcapol Church. |

The government warehouses have all been destroyed so there is no chance of filling our haversacks. This city's citizens are busy looking for food themselves. There is little here to sustain us and we dare not stay long.

|

| Burning of Columbia. |

We continue to decrease in size. We have lost most of my regiment. The rest of the Twelfth left the party north of Columbia except for Lieutenant Colonel Kinsler and as his home is here, when I leave, I will be the only one left. I shall have to travel with those from the First as only they remain from our original party which left Lancaster on Wednesday last.

I hope that we leave this wretched place soon. There is nothing to keep us here. Things will be better in Charleston.

I Send You These Few Lines.

Tooms and those he is traveling with are largely following, in reverse, the route that Sherman's army took as it moved through South Carolina from Savannah. The XVth Corps, of Sherman's army passed closest to Camden on their march north.

|

| Major General John A. Logan, commander of XV Corps. |

Columbia suffered greatly during the closing days of the war. A great deal of the city was gutted by fire. Who started the fire has long been a source of heated, emotional contention. Sherman did order that buildings and supplies of military use to the Confederacy be burned but not a general conflagration. As with the burning of Richmond in April, things got out of hand. High winds blew the fires out of control. Some fires were supposedly started by Wade Hampton's cavalry as he ordered the destruction of cotton bales. Whomever started the fires aside, once the winds kicked in, the fire went off of itself. Tooms' anger against the Federal forces is perhaps unjustified.

|

| Major General Wade Hampton. |

The fleeing Jefferson Davis is reunited with his wife and family 150 years ago today on the banks of the Oconee River in the woods northeast of Abbeville, Georgia.

|

| Jefferson Davis |

|

| Varina Davis |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)